----

Housman, A.E. 1896. A Shropshire Lad - Bartleby.com

www.bartleby.com › Verse › AE Housman

Bartleby.com's online publication of the classic 1896 edition of A. E. Housman's "Contents. Housman, A.E. 1896. A Shropshire Lad - Bartleby.com

www.bartleby.com › Verse › AE Housman › A Shropshire Lad

A Shropshire Lad. ... Wake: the silver dusk returning · Oh see how thick the goldcup flowers · When the lad for longing sighs · When smoke stood up from Ludlow ...| A. E. Housman (1859–1936). A Shropshire Lad. 1896. |

| Contents |

2012.1.22

A SHROPSHIRE LAD: LXII (Alfred Edward Housman )

Pub

引

A SHROPSHIRE LAD: LXII

Terence, this is stupid stuff...

Alfred Edward Housman - Selected Poems from Allspirit

allspirit.co.uk/housman.html - 頁庫存檔 - 翻譯這個網頁

Say, for what were hop-yards meant, Or why was Burton built on Trent? Oh many a peer of England brews Livelier liquor than the Muse, And malt does more ...

Say, for what were hop-yards meant, Or why was Burton built on Trent? Oh many a peer of England brews Livelier liquor than the Muse, And malt does more than Milton can To justify God's ways to man. Ale, man, ale's the stuff to drink

hopyard

n.A field where hops are raised.

hop[hop2]

発音記号[hɑ'p | hɔ'p]

[名]

1

(1) 《植物》ホップ:クワ科多年生つる草の総称.

(2) ((〜s))ホップ:乾燥したホップの実;ビールの芳香苦味剤・強壮薬用.

2 [U]((米俗))アヘン(opium);麻薬中毒.

3 ((米・豪俗))ビール.

━━[動](〜ped, 〜・ping)(他)〈(アルコール)飲料に〉ホップで風味をつける.

━━(自)ホップの実を摘む.

This is London from dawn till night

This is London from dawn till night ( 1953photo books of the world)

---

Considering a straight history of a complicated poet

A.E. Housman

A Worcestershire lad

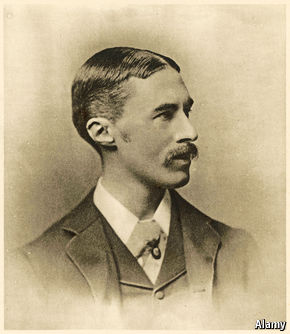

IN FEBRUARY 1896, a slim volume of 63 poems was published: 500 copies at half a crown each. Their author, A.E. Housman, had had to pay £30 towards publication. (“Vanity,” he confessed, “not avarice, is my ruling passion.”) Sales were sluggish despite a handful of favourable reviews, and the first printing didn’t sell out until two years later. The volume remained in print, however, and slowly but steadily sales picked up. The poems, set in an idealised English countryside and imbued with a yearning melancholy, struck a chord not just in England but in America. By 1918 “A Shropshire Lad” was selling 16,000 copies a year.

Alfred Edward Housman was not a Shropshire lad but a Worcestershire one. His mother died as he turned 12, an event which left the seven Housman children in the care of their genial but madcap father, and which would gradually lead Housman to reject Christianity. He left the local grammar school garlanded with prizes, and went to Oxford with an open scholarship to study classics. He is perhaps the only person ever to have got a first in his second-year exams, and then entirely failed his finals.

“So Alfred has a heart after all,” a member of his family remarked after reading “A Shropshire Lad”. He certainly had, and it had been broken by a fellow undergraduate, Moses Jackson. As Jackson was heterosexual, the love was unrequited—possibly never even expressed—but it was the great passion of Housman’s life, and it left him almost incapable of intimacy. He could, said his Times obituary, be “so unapproachable as to diffuse a frost”. E.M. Forster was not the only person to find his attempts at friendship brutally rebuffed, and when Housman died in 1936 he wore an expression of “proud challenge”.

So much for the man. But Peter Parker’s new book is much more than a biography, and having lured us into Housman’s life with a magpie’s eye for detail, he then sets out on a tour of Housman Country—not a geographical area but a landscape of the mind in which “literature, landscape, music and emotion” all contribute. He casts his net wide to encompass, among much else, the feelings of an increasingly urbanised population about the English countryside; the development of the Youth Hostels Association and the Ramblers’ Association; the publication of the Shell County Guides; the attitudes of other writers, including George Orwell, Rupert Brooke, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden and Ted Hughes towards Housman; and the part Housman played in the English musical renaissance.

But it was ordinary people (chiefly men) that Housman longed to reach through his poetry, and thousands of soldiers in both world wars left home with copies of “A Shropshire Lad” in their breast pockets, where Housman hoped they might stop bullets. The poems remained precious to some for years after the war was over.

Today, Housman’s influence continues to be felt, not simply among contemporary writers—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Alice Munro and Tom Stoppard among them—but in popular culture, from “Inspector Morse” to “The Simpsons” and “The Archers”. Among rock singers, Mr Parker considers Morrissey the musician “who most embodies” Housman’s spirit.

After 120 years, “A Shropshire Lad” has never been out of print. “Some men are better than their books,” Housman believed, “but my books are better than their man.” What this wry, shy genius created in one slim volume was not simply a collection of moving poetry but a “gazetteer of the English heart”.

-----

What the wry, shy A.E. Housman created in "A Shropshire Lad" was not simply a collection of moving poetry—but a "gazetteer of the English heart"

沒有留言:

張貼留言