From John Fowles with love: how the author’s first true romance and lost poem came to light

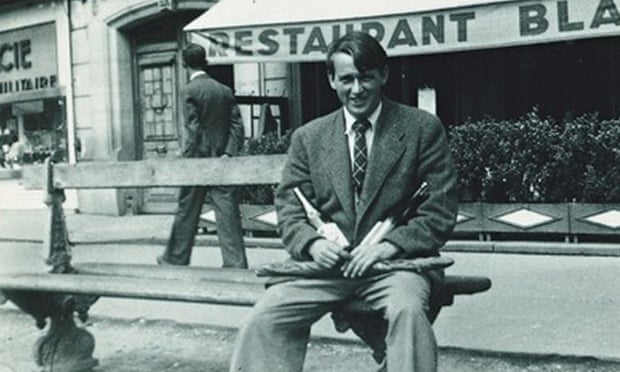

In 1951 John Fowles was an assistant teacher at Poitiers University when he fell seriously in love for the first time. More than 60 years on, Mike Abbott meets the student he fell for and uncovers the unpublished poem he wrote for her

John Fowles died 10 years ago. The two volumes of his Journals were published just before and after his death. At the time, they stirred up coverage and debate because they were extraordinarily candid and indiscreet. However, in the past decade the dust has settled and, as is the nature of things, the name of this literary superstar from the 1960s and 70s is now rarely mentioned.

I was recently leafing through the first volume of the Journals and was drawn to Fowles’s description of his relationship with a young French student at Poitiers University, where he was a teaching assistant. It was his first academic post and he was 24 years old. The episode opens on Sunday 7 January 1951:

Sitting about in a cafe most of the day. People bore me profoundly and desperately. There is one girl who is beginning to interest me fractionally. She attacks me all the time, and I attack her, and we’re not bored while we’re doing it.

Thus began an intense six-month romance that clearly made a major impact on the young author. It was his first serious love affair. The student was called Ginette Marcailloux and she was 23 years old. He describes her as a dark vivacious meridional beauty, interesting, intelligent and quick-witted. Soon he was confiding to his journal: “I feel closer to her than anyone else I have everknown.” There is endless sensual kissing and caressing, dancing at the student centre, moonlit walks in the surrounding countryside. “The next stage is bed. She is too virtuous for that.” Fowles devotes more than 70 pages to the detailed description of them growing ever more intimate through the spring. He even begins to contemplate marriage.

Then my eye was caught by a footnote saying that Limoges was Ginette’s hometown. I live in Limoges. On a whim I picked up the phone book to see if there were any Marcailloux listed, although I thought that her maiden name would have since been changed by marriage. My finger ran down the small print … Marat, Maraval, Marbouty … and then stopped. There was only one Marcailloux. And it was Ginette.

It took me a few days to summon up courage to pick up the phone. How do you speak to a lady of 87 about a love affair that took place 64 years previously? I dialled the number and played it straight; I introduced myself and asked if she knew John Fowles in Poitiers in the early 1950s. There was a long pause and I expected the phone to go down. But then a faint voice said: “Yes I knew John Fowles.” What went through her mind at that point? A complete stranger interrupting her quiet life with questions from a lifetime ago. We chatted a bit and she seemed not to be too disturbed by my impertinence. We arranged to meet the following week.

And so began a conversation that transported us back to 1951 with a description of a young poet/novelist just starting his career. Ginette is now a neat but frail lady, hard of hearing but with that sharp intelligence still intact. She became an English teacher and never married. She has no surviving family. She described Fowles as a difficult person, confident but reserved, ironic and proud. He was writing constantly, poetry and prose. It was obvious then, she said, that he wanted to write novels that were challenging and different.

It is clear from his Journals that, as summer approached in 1951, his love had begun to cool. Their relationship effectively ended at the close of that academic year as he was leaving Poitiers. It was a difficult parting, and he reports Ginette saying “I wish I had never met you”. He describes a final meeting on 22 August in which “she had never seemed prettier to me”, a “just and dignified letter” from Ginette on 5 September, and, on 6 December, another letter: “for her all is over, dry bones … end is inevitable”. On 26 December, on the eve of his departure for Greece and a new teaching job, he looks over his shoulder briefly: “I shall not find a Ginette again”.

She noticed when he became famous many years later, and did read his novels. I asked if she had any letters or photographs from the Poitiers period. “He gave me a passport photo but I lost that ages ago. I had lots of letters from him but I had a clear out not so long ago and they’ve all gone.” She seemed happy to talk but there remained a formality and a reticence, and I didn’t want to impose any longer. We agreed to stay in touch.

A few weeks later Ginette called me. “I think I’ve found something that you might want to see. Come round.” On her table was a thin piece of typed paper; a paragraph of prose and a poem. The prose is a mixture of French and English, which was how John and Ginette spoke together.

Occasional verse. A souvenir. Without value as verse. I am in the process of typing my complete work. Boring work but necessary. If I die tomorrow no one will be able to decode it. It’s the ransom of likely glory, or the stupidity of certainly being forgotten. Do you remember that evening? Sometimes I write a poem just to remember something, a need to keep a souvenir. Even if the poetry is bad, it still has a sort of value as a point of reference.

Then there was the poem, with no title but an inscription at the bottom: Café de la Paix 14.1.51. Ginette explained: “The Café de la Paix was where all the students used to gather together. It’s a poem from John to me.”

Back home I immediately cross check with the Journal. And there, as part of the same entry for Sunday 7 January when he first mentions his “fractional interest” in Ginette, is the following:

Feel ill and spend the whole evening playing dice with Ginette and Phil. Ginette, dark, vivacious in a not too gleaming way. With fine dark malicious eyes. She treats with a certain mock respect our student-lecturer relationship. I taught them liar’s dice. We played till midnight.

Ginette is puzzled why anyone would be interested in this story. On the face of it, it is of minor interest; a footnote to a footnote in literary history. But on the other hand it is a chance encounter that has opened a door into a room full of memories. I am holding a fragile piece of paper, an unpublished poem that marks the beginning of the first real love affair of a celebrated British writer. I have a picture of a French provincial cafe full of noisy students in a fog of filterless Gitanes, drinking coffee and cheap red wine and arguing about Jean-Paul Sartre. And in the middle of it are John and Ginette playing dice, falling in love. It’s a piece of paper that almost disappeared, but which survived. If I don’t write it down now, it will be lost forever.

游常山

E. M. Foster乍看好讀,其實蠻「陳映真」的,對英國固化的階級,有很深的批判。我反覆讀了幾次【霍華大宅】(Howard’s End),還是進不去英國階級愛恨情仇的世界。

跨文化的閱讀,沒有那麼容易,讀懂英文字面,讀不懂背後一整套的社會文化架構的totality

E. M. Foster是英國當代最優秀的小說家,我要感謝英語世界的電影製片體制,從近三十年前的【印度之旅】【窗外有藍天】【此情可問天】(原著就是Howard’s End)…否則我們光是掌握長篇故事的「梗」就很大力氣

詮釋文本背後的社會真實?

這經驗很有意思.多少表示電影比較容易懂.通常是原著給讀者更多的想像空間.建議游兄試試" 法國中蔚的女人" 電影略去很多的"社會-文化"層面.......

Hanching Chung 哈哈 果真如此? 下會找到筆記本或可借你. 作者的房產很大--Jane Austen 的小說描述過的地方---身後願捐給University of East Anglia - UEA當"寫作中心--- 可憐的英國大學. 評估之後放棄.因為無力維持之. 我很關心後來如何了.......- http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/07/john-fowles-house-landmark-trust-restoration

Author John Fowles's Dorset house to become a centre for young writers

Landmark Trust sets to work on historic seaside building, home of the author of The French Lieutenant's Woman until his death

John Fowles poses at his home in Lyme Regis, Dorset, in 1985. Photograph: David Levenson/Getty ImagesIn 1999, six years before he died, the novelist John Fowles wrote that despite its beauty, acres of garden, ravishing views and historic interest – not only as his home but that of the pioneering Georgian businesswoman, Eleanor Coade he – was failing to give away his beloved house in Lyme Regis, Dorset.

He dreamed the Grade II* listed Belmont House could become a centre "for young writers and artists" who would be as inspired by its beauty and history as he. The main windows of the room where he wrote look straight out to sea, or steeply down to the Cobb where he sent his melancholy heroine, The French Lieutenant's Woman, on her solitary walks. His desk, possibly to give him some defence from the distractions of such a view, was set at right angles to it.

He had lost count of the institutions he approached, he wrote sadly, including the University of East Anglia, famed for the creative writing course co-founded by his friend Malcolm Bradbury, of which he was an honorary graduate. None felt capable of taking it on.

One American demanded assurance that the property could never suffer from landslip: since the house is perched halfway up a cliff on the Jurassic Coast, where for centuries fossil hunters have flocked to pry treasures from the rapidly eroding slopes, he could give no such promise.

Now, though there are many more cracks in walls and terrace, and the garden is even more of a jungle than he affectionately complained of, his wishes may come true.

The Landmark Trust, which restores historic buildings, has bought Belmont from Fowles's widow Sarah, and is fundraising to restore it not just as a holiday rental like its other properties, but a residential centre for young writers. This time the University of East Anglia, whose graduates include Anne Enright, Kazuo Ishiguro and Ian McEwan, has said yes.

Discussions are also ongoing with Royal Holloway and other academic institutions.

The move is an innovation for the Landmark, but one which its new director Anna Keay hopes to build on at other properties.

"I love the thought of bringing that literary life back into the house, and making the whole place not just a nicely restored old building but a living memorial to Fowles and his work," she said.

"The history of this house is already so rich and multilayered, it's nice to think of adding another chapter."

Many of the trust's properties are eccentric, including a pineapple-shaped summer house, a palatial water tower and a pigsty designed as a Greek temple.

The extraordinary facade of Belmont, a plain Georgian box bristling with applied decoration including sea monsters, urns and a head of Neptune, will fit perfectly into the portfolio.

The house was a summer home and a sort of three dimensional trade card for the formidable Eleanor Coade, who manufactured classical figures, architectural ornaments and garden statues at Coade's Artificial Stone Manufactory in Lambeth, out of an artificial stone which has proved astonishingly tough.

The facade is sadly damp-stained and cracked, and inside ceilings, verandah and windows are propped to prevent collapse: the fierce little dolphins, made in the 1780s, are as crisp as if made yesterday.

Fowles, who was for many years curator of the Lyme Regis museum, was fascinated by Coade – "that very rare thing, both an artist and a successful early woman industrialist".

The trust has now won planning permission to demolish the shabby stumps of once ornate Victorian wings added by later owners, but will keep a charming observatory added in the 1880s by a Victorian GP, Richard Bangay.

They plan to restore the surviving mechanism on which the entire roof once rotated and opened, and reinstate a telescope – and, they hope, some visiting astronomers too.

Another rare survivor, a little stable building, will become an exhibition space telling the story of the house and its owners.

When Keay first saw the building she felt she had been there before. "Everything about it, the views, the steep scramble down through the garden to the Cobb, even the fact that there really had been a telescope like the one the doctor in the French Lieutenant's Woman uses to spy on women on the beach, seemed so familiar it was almost eerie."

In fact, although Fowles had obviously already paced every inch of the settings he used in the novel, he bought the house just after he finished the book which became even more famous as the 1981 Harold Pinter-scripted film starring Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons.

In his journal for September 7 1968 he recorded both the house and the telegrammed reaction of his publisher, Tom Maschler.

"I have offered £18,000 for Belmont House. 'The French Lieutenant's Woman is magnificent, no less. Congratulations. Letter follows. Love Tom'. That's a relief."

John Fowles--The Journals, Volume I

www.fowlesbooks.com/JournalsI.htmHome. John Fowles-The Journals, Volumes I & II Now Available. Both volumes of John Fowles' amazing journals have now been published, by Jonathan Cape ...

Ian Sansom reviews 'John Fowles' edited by Charles Drazin and ...

www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n09/ian-sansom/his-own-peakJohn Fowles: The Journals, Vol. I edited by Charles Drazin Cape, 668 pp, £30.00, October 2003, ISBN 0 02 240691 3; John Fowles: A Life in Two Worlds by ...

The Journals. Volume Two: 1966-1990 - By John Fowles - Books ...

www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/books/review/Campbell2.t.html?...allOct 29, 2006 - When his journals were published, John Fowles chose not to delete disobliging remarks about friends.

The Journals of John Fowles: v.1: Vol 1: Amazon.co.uk: John Fowles ...

www.amazon.co.uk › ... › Novelists, Poets & Playwrights › NovelistsThe Journals of John Fowles: v.1: Vol 1: Amazon.co.uk: John Fowles, Charles Drazin: Books.

Journals Vol II: v. 2: Amazon.co.uk: John Fowles: Books

www.amazon.co.uk › ... › Novelists, Poets & Playwrights › NovelistsTrade in Journals Vol II: v. 2 for an Amazon.co.uk gift card of up to £0.25, which you can then spend on millions of items across the site. Trade-in values may vary...

John Fowles - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_FowlesJohn Robert Fowles (/faʊls/; 31 March 1926 – 5 November 2005) was an English .... Writings; (2003) The Journals – Volume 1; (2006) The Journals – Volume 2 ...

沒有留言:

張貼留言